Strong interest in traditional printmaking reflects a new generation’s appreciation for artistic processes and craftsmanship.

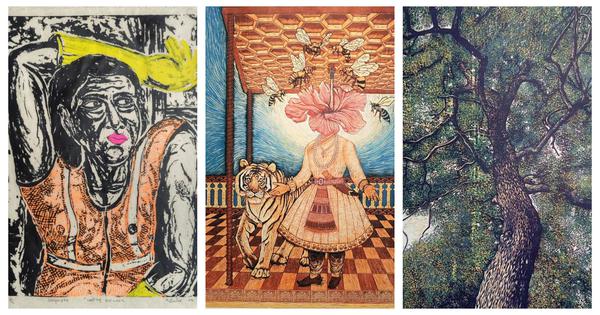

In an era dominated by digital creation, printmaking stands out as a tactile and contemplative medium. This was evident in a recent exhibition titled Editions, curated by Annapurna Madipadiga and Attri Chetan, which showcased the work of 30 young artists from 14 states. The event, held at the State Art Gallery in Hyderabad from September 19-28, highlighted the importance of process in art, alongside the final product.

Madipadiga expressed the addictive nature of printmaking, stating, “To explore, draw, burnish, scrap, start from scratch is a unique joy.” The exhibition offered a broad perspective on printmaking, focusing on its technical and aesthetic aspects. It featured various mediums, including cyanotype, zinc plate etching, linocut, lithography, and serigraphy, as well as diverse techniques such as intaglio, relief, screen printing, and aquatint. This variety emphasizes the historical depth and formal diversity of the medium.

According to Madipadiga, printmaking is often seen as one of the most intricate art practices due to its long and laborious process, which contributes to its uniqueness. Each print, even within an edition, exhibits subtle variations that distinguish it from others. The technique demands patience, planning, and precision, qualities that are crucial in an artist’s engagement with printmaking.

Historically, printmaking was introduced to India in the late 15th century by the Portuguese, who established presses for printing religious texts. Over time, this medium evolved into a powerful visual language for expression and resistance, particularly during the Indian freedom movement when lithographs conveyed nationalist messages. Prominent figures like Indian painter Raja Ravi Varma further popularized printmaking by producing affordable lithographs and serigraphs, which brought images of deities into homes across the country, democratizing art access.

Printmaking gained additional momentum at Rabindranath Tagore’s Santiniketan university, where artists like Nandalal Bose created works that are now highly valued in art auctions. In the pre-photography era, prints and lithographs documented social life, capturing the dynamics of a changing nation. However, sustaining this practice has been challenging due to the complexities involved and a lack of interest from collectors.

Editions showcased the diverse interpretations of printmaking by different artists. For instance, Narendra Kumar utilized handmade paper from sugarcane pulp, while Charandas Jadav printed observations from red-light districts on truck mud flaps. Agwma Basumatari innovatively employed discarded debit and credit cards to craft miniature artworks, whereas Raja Boro created intricate woodcut miniatures depicting Shantiniketan’s landscapes. Shantanik Modak, inspired by miniatures, used screen printing to portray panoramic views of the Himalayas on postcards, capturing the vibrancy of the hills.

Archi Bharadwaj from Rajasthan produced striking screen prints reflecting her train travels and even created a graphic novel using the technique. She described the labor-intensive process as therapeutic, emphasizing the unique expression that printmaking offers compared to other art forms. Despite the challenges, the exhibition highlighted how a new generation of artists is embracing printmaking, valuing the process as much as the final product. This commitment serves as a quiet act of resistance against the fast pace of modern life, reminding us that beauty often emerges from patience, pressure, and time.