Shahid Siddiqui’s book uncovers the dynamics between Rao and the enigmatic figure Chandraswami.

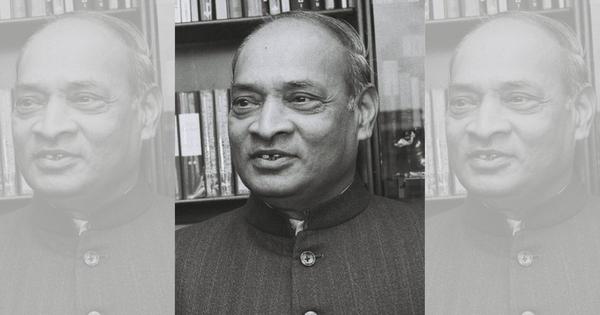

During the early 1990s, India faced a dire economic crisis marked by plummeting foreign exchange reserves and soaring inflation. When PV Narasimha Rao assumed office, the country was grappling with economic instability, having seen reserves drop below $1 billion, barely enough to cover three weeks of imports. Inflation rates peaked at 16.7% in August 1991, exacerbated by the Gulf War and fiscal mismanagement. In response to the looming threat of default, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) pledged gold reserves to secure emergency loans from international banks, an act that sent shockwaves through the nation.

Despite the overwhelming challenges, Rao was chosen to lead the government amid expectations of failure. He approached the situation with a calm demeanor, taking bold yet unpopular steps without seeking immediate electoral approval. One significant action was the devaluation of the rupee, which Rao and Dr. Manmohan Singh executed shortly after taking office. The rupee was devalued by 9% on July 1, 1991, followed by an additional 11% two days later. This decisive move was made possible by Rao’s position as head of a minority government, allowing him to implement drastic measures without immediate political repercussions.

Rao’s relationship with various political figures was complex. While he informed leaders like Atal Bihari Vajpayee and those from the Left Front about economic decisions, he often did not consult Sonia Gandhi, which caused discontent among her close associates. On July 9, 1991, Rao addressed the nation, preparing citizens for necessary sacrifices as he embarked on the challenging task of economic repair. His partnership with Dr. Singh marked a pivotal shift toward liberalization, privatization, and globalization, a process Rao acknowledged as a continuation of policies initiated by Rajiv Gandhi.

In the backdrop of these political maneuvers, the figure of Jagadacharya Chandraswami emerged as a powerful influence. Born Nemi Chand Jain, he was a charismatic individual who claimed to possess telepathic abilities, impressing political leaders including Indira Gandhi. Chandraswami’s networking skills allowed him to forge connections with influential figures, including Saudi arms dealer Adnan Khashoggi, facilitating a mutually beneficial relationship that spanned various sectors.

Chandraswami’s growing influence reached a point where his recommendations were sought after for significant government appointments. Rao, while navigating the complexities of his leadership, could not afford to overlook Chandraswami’s power. One instance highlighted the extent of this influence when a senior IAS officer sought Rao’s assistance for a coveted position, only to find that Chandraswami’s intervention proved decisive in overcoming objections related to the officer’s personal life.

Rao’s tenure, therefore, can be seen as a delicate balancing act between managing economic reform and navigating the intricate web of relationships shaped by figures like Chandraswami. This interplay of power dynamics not only defined Rao’s leadership but also left a lasting impact on the political landscape of India during a critical period of transformation.