Exploring the significance of Maulana Daud’s ‘Candāyan’ in the evolution of Hindi literature

A growing number of historians of Hindi literature argue that the origins of the Hindi literary tradition can be traced back to the Sufi romance, particularly the Candāyan, composed by Maulana Daud in 1379 CE. This work is considered pivotal for several reasons. Firstly, it is recognized as the earliest known piece in a vernacular register that would remain in use for literary purposes for the next five centuries. Secondly, it utilizes specific meters and verse forms, such as the caupaī and dohā, which later became closely associated with bhāṣā literature. Furthermore, it marks the inception of a genre that would hold a significant place in the vernacular literary landscape until well into the nineteenth century.

While there is some scholarly debate regarding the true beginnings of Hindi literature, with some locating its origins in different centuries or genres, the Candāyan stands out if one considers Sheldon Pollock’s view that the act of writing and the conscious identification of poetry as literature are essential to the formation of literature itself. Daud’s work is particularly notable as it is recognized as the first piece in a north Indian vernacular deliberately crafted as literature.

Prior to the Candāyan, there were various forms of vernacular expression, notably in the malfuẕāt, which are dialogic memoirs capturing the conversations and sermons of Sufi pīrs. For instance, the Nafāʾis al-Anfās, created by Rukn al-Din between 1331 and 1337 CE, and the Shamāʾil al-Atqiyā from the 1330s, also by Rukn al-Din Kabir, recorded some “Hinduī” verses. Although these malfuẕāt were composed just before Daud’s work, their historical accuracy remains difficult to establish.

Amir Khusrau, a contemporary poet, further contributed to this literary landscape with his macaronic verses, which mixed vernacular and Persian. His works, while significant, lack early manuscript copies, making it challenging to determine their original form. However, it is clear that the nature of Daud’s project was different. As Aditya Behl posits, the Candāyan signifies the deliberate creation of a new genre.

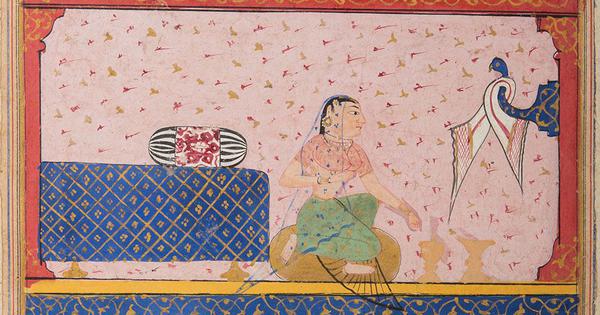

Daud adapted the oral epic of Prince Laur and Princess Chanda, transforming it into a written narrative enriched with literary and rhetorical elements from both Persian and Indic traditions. His incorporation of Sufi symbolism allowed the poem to function simultaneously as an erotic romance and an allegorical representation of Sufi mysticism.

Unlike earlier written forms of bhāṣā, Daud’s work was conceived as a literary piece from the outset. He was keenly aware of the importance of transitioning bhāṣā from orality to written form, capturing the performative aspects of his composition. In the Candāyan’s opening, modeled after Persian masnavī, Daud lauds his patron, Juna Shah, emphasizing his literary acumen and cultural heritage.

Daud’s language reflects a nascent movement to redefine the vernacular semiotic landscape. His use of the term pothī encapsulates various concepts of text, scripture, and manuscript, symbolizing both Islamic and Indic texts. This term often referred to unbound folios made of palm leaf or paper, which were common formats for written works in the early north Indian sultanates.