A Hill Resident’s Reflection on Progress, Memory, and the Mountains’ Warnings

The roar always comes before the silence.

On a grey August morning in Dharali, the Bhagirathi swelled beyond its banks. A cloudburst high in the folds of the mountains sent torrents racing down, carrying boulders, logs, and memories. Homes that had stood for years crumbled in minutes. And then, as quickly as it came, the water quietened — leaving behind a silence that was not peace, but absence.

For those of us living in the Himalayan towns — Mussoorie in my case — such stories no longer feel like distant news. They feel like foreshadowing. Dharali, Himachal’s Kullu, cloudbursts in Uttarkashi, landslides in Joshimath, sudden flooding in Dehradun, and even Delhi or Gurgaon under water — all tell us that nature has begun speaking louder than our machinery.

And just this week, the mountains spoke again. In Tharali, Chamoli, a devastating cloudburst tore through the tehsil market and homes, taking the life of a young girl, leaving others missing, and burying the SDM’s residence under debris. Rescue teams are still searching, even as experts have been called in to study what went wrong. In Harsil, debris blocked the Bhagirathi near the army camp and helipad, creating a one-kilometre-long lake — a silent wall of water, beautiful yet terrifying, holding the valley hostage. Near Yamunotri, Jankichatti, debris blocked the Garhgad stream, forming a 20-ft-deep lake that flooded homes and hotels, forcing over 300 evacuations. And in Niti Valley, toward the China border, the Dhauliganga was similarly dammed by debris, creating yet another fragile lake that the BRO and army now rush to drain. Each of these new calamities is not an isolated event, but another verse in the same poem of imbalance.

The Wisdom of Where We Once Built

When I was younger, I noticed something about old Garhwali villages. They seemed almost shy of the rivers, choosing instead to perch on gentle slopes or ridgelines. Fields stepped down like green staircases, homes faced the sun, and water was drawn from springs and channels rather than from a flood-prone bank.

It wasn’t an accident. Generations knew the moods of the hills — that rivers here are fed by glaciers and storms, swelling without warning. They knew that the land itself was young and restless, shifting beneath us with each monsoon. And so they built with space for the river to rage, with distance to let landslides fall away harmlessly.

Contrast that with today’s popular tourist hubs. Hotels pressed right to the edge of river curves. Cafés jutting over streams on concrete stilts. Resorts sprouting beside highways that were once mule paths. It is not that these places lack beauty — they have plenty — but they stand in zones the elders would have quietly avoided.

Acceleration: The Blessing and the Burden

In Uttarakhand, development has a new face: ropeways to hill temples, four-lane highways cutting through slopes, expressways promising Delhi–Dehradun in just two and a half hours, and a proposed Char Dham railway linking high-altitude pilgrimage sites.

These projects are designed with good intentions — to ease travel, boost the economy, and allow more pilgrims to visit without strain. They are marvels of engineering, symbols of connectivity in a region where roads once closed for weeks due to landslides.

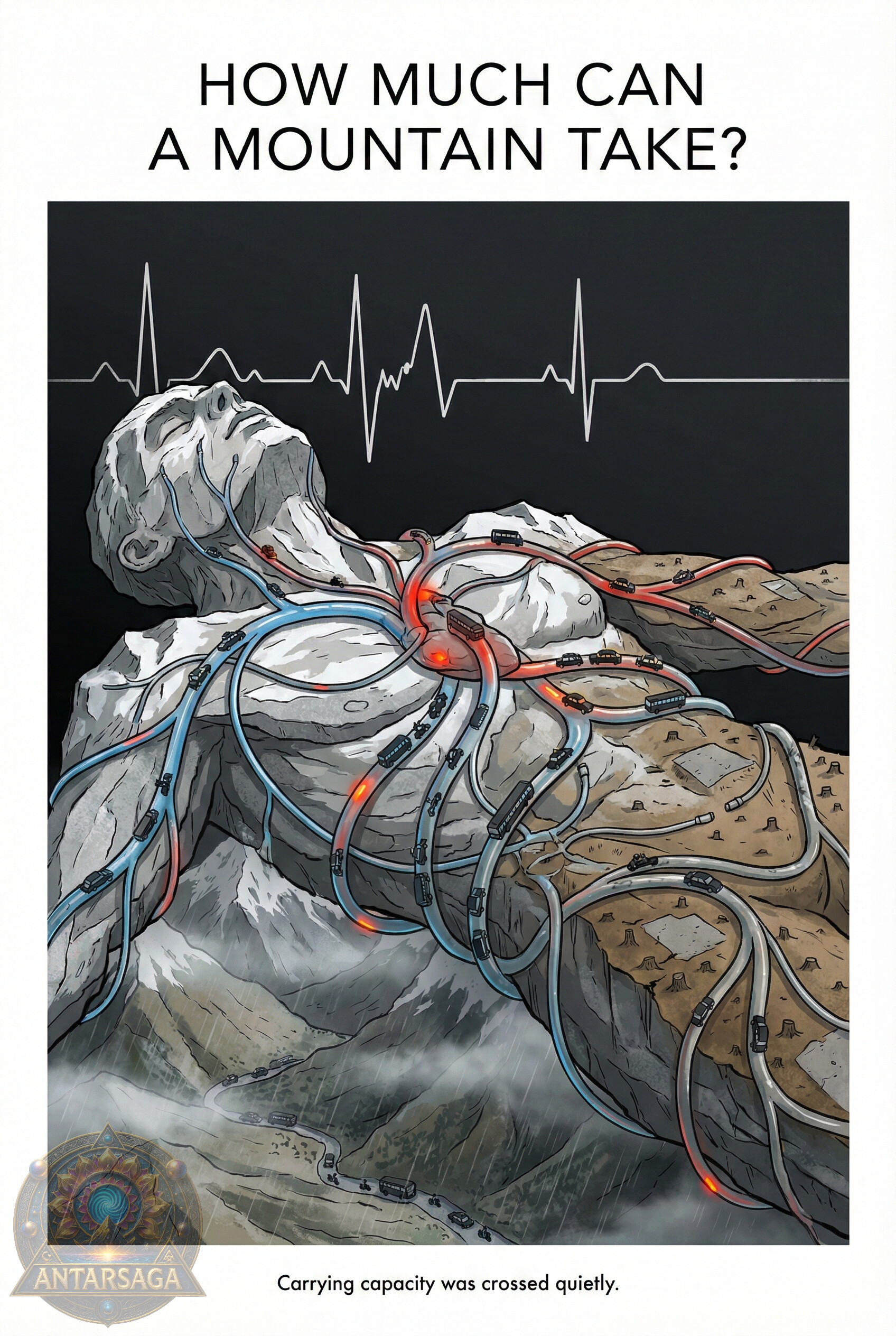

But here is where the laws of cause and effect echo in the mountains: every action has a reaction. Greater access brings greater footfall, which brings heavier infrastructure, which asks more of the land. The Himalaya is not an infinite sponge; it is a living, breathing system with limits.

The more we accelerate, the more we must prepare for the reaction. If the preparation is absent, the reaction will arrive as erosion, flooding, slope failure — not as an act of malice from nature, but as a consequence of imbalance.

The Hills’ Silent Warnings

Those who live here see the small signs first.

A crack widening in a retaining wall. A seep of water where none flowed before. A boulder that shifts a little lower each monsoon. Springs that dry earlier than they used to.

This week’s calamities are louder warnings. Harsil’s lake, stretching a kilometre behind a wall of debris. Yamunotri’s artificial reservoir, flooding homes and hotels. Niti’s silent lake, threatening to break without notice. These are not natural lakes; they are accidents waiting to happen. When such temporary dams collapse, they unleash floods more violent than any dam release, leaving villages downstream no time to escape.

In Mussoorie too, we have watched slopes give way under sudden downpours. We’ve seen landslip scars widen when drains clog and water has nowhere to go but down, carrying the earth with it. Our geology is young, still rising from the tectonic restlessness that created it. Every cut we make into a slope, every riverbank we claim for parking or promenade, tips the balance a little more.

Why a Single Strategy Won’t Work Across India

India’s landscapes are too varied for one-size-fits-all development.

What works in Kerala’s flood-prone lowlands — stilted homes, water channels, paddy buffers — won’t suit the fragile spurs of the Himalaya. The broad plains of Punjab or Gujarat can bear highways and industrial parks in ways Arunachal’s river valleys cannot.

In the north, especially in the Himalayan arc, building near rivers and on steep slopes demands absolute restraint. In the Indo-Gangetic plains, it is floodplains and drainage corridors that must remain open. In the west, it is water conservation and heat resilience; in the east, cyclone buffers and mangrove belts.

Trying to impose one common “national model” without regional nuance risks repeating the same mistakes in new forms.

What Building Without Breaking Could Look Like

The point is not to stop building. It is to build as though we intend to remain here for centuries. It means:

Riverside restraint: No permanent structures in the high-flood mark zone. Keep river corridors free to expand during cloudbursts.

Slope-sensitive design: Roads and hotels should follow contour lines, not cut across them. Natural drainage must be preserved or improved.

Tourism caps in sensitive zones: Spread the load. Promote eco-lodges and homestays in stable terrain instead of concentrating visitors in fragile choke points.

Green highways in truth, not just name: Road expansion should include proper slope stabilization, bio-engineering, and regular drainage maintenance.

Pilgrimage infrastructure with buffers: Place parking, lodges, and amenities a safe distance from temples and river confluences, with shuttle or ropeway transfers.

Urban forest cover: In cities like Dehradun, treat green spaces as flood buffers, not just decoration. Plant native species that anchor soil and regulate runoff.

The Emotional Reality

I write this not as a policy expert but as a resident who loves these hills. I understand the desire for faster travel, for more visitors, for economic growth. Tourism feeds families here — shopkeepers, taxi drivers, guides, porters. But all of it depends on the hills remaining standing, the rivers remaining clean, the forests remaining alive.

Yet the human cost is mounting. This monsoon season alone, Uttarakhand’s losses are estimated at nearly ₹3,000 crore. More than 70 lives lost, hundreds injured, dozens still missing. Families displaced, schools damaged, farms washed away. These are not statistics — they are neighbours, children, shopkeepers, teachers.

If we build in a way that undermines the very beauty people come for, we will end up with the worst of both worlds — fragile infrastructure and a diminished environment.

A Closing Appeal

I believe progress is not the enemy of nature — imbalance is. The Himalaya does not reject our roads or ropeways; it simply asks that we place them with wisdom, patience, and humility.

The elders who built on ridges and plateaus did not have engineering degrees, but they read the slopes like a map and the rivers like a diary. We have satellites, 3D models, and climate data — yet sometimes, we ignore what they knew instinctively: that safety is not found in defying nature, but in moving with it.

If we can blend that inherited wisdom with our modern capability, we can indeed build without breaking. We can hand the next generation not just a network of roads and railways, but a living land — a Mussoorie where the springs still flow, a Dharali that never sees another black-water morning, a Tharali that never drowns in silence again, a Yamunotri and a Harsil where rivers run free without sudden lakes, a Niti where valleys stay open and safe.

For in the end, these hills are not just scenery. They are home. And homes, if they are to last, must be built with care.