Dugald Mackichan’s memoir reflects his complex relationship with colonial Bombay and its people.

Dugald Mackichan, a Scottish missionary from the Free Church of Scotland, embarked on his journey to Bombay in February 1875, at the age of 24. Initially, his mission was to serve the community, but over the next 45 years, he established himself as a prominent academic and a scholar of both Sanskrit and Marathi. His reflections on life in Bombay are captured in his book, Forty-Five Years in India, which combines biographical elements with a historical account of the city during a period marked by colonial rule and significant social upheaval.

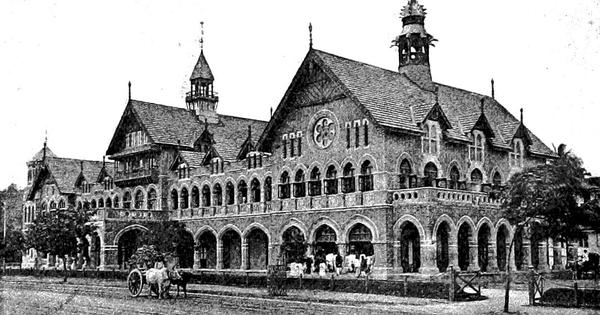

Mackichan’s tenure in Bombay began with his appointment as the principal of Wilson College, where he succeeded its founder, John Wilson. His academic influence extended further as he served four terms as vice-chancellor of Bombay University. His writings, particularly about the political and social dynamics of the time, offer valuable insights, including his observations during the 1896 plague outbreak. Mackichan’s account is notable for its depth and detail, revealing not just the events but also the societal responses to them.

Among the figures he admired was Lord Reay, the governor of Bombay from 1885 to 1890. Mackichan praised Reay for his efforts to foster closer relationships between Europeans and Indians, noting the inclusivity at Government House, where Indian guests were increasingly welcomed at social events. Mackichan himself shared a critical view of the prevalent racial segregation in public transportation, particularly the separation of railway coaches for Europeans and Indians. He argued against the justifications for this division, highlighting the adaptability of Indian travelers and expressing his appreciation for their company during journeys.

Despite his fondness for Indian culture and his institution’s progressive admissions policy, Mackichan’s views on Indian independence were complex and often contradictory. His critique of revolutionary figures like Vasudev Balwant Phadke reflected a reluctance to support the independence movement. He characterized Phadke’s actions during the famine of 1877 as banditry rather than a legitimate uprising, suggesting that the revolutionary’s notoriety was more about criminality than a quest for freedom. Mackichan’s stance indicated a belief in the need for order and stability, even in the face of colonial injustices.

During his long stay in Bombay, Mackichan also observed the devastating impact of the bubonic plague. He described the mass exodus from the city and detailed the rising demand for wood for funeral pyres, painting a vivid picture of the human suffering that accompanied the epidemic. His reflections included a recognition of the skepticism many Indians had towards medical interventions like inoculation, which he noted was perceived with suspicion, particularly among Hindu communities.

Despite his efforts to connect with the local population through language and cultural understanding, Mackichan often found himself frustrated by the colonial authorities’ lack of engagement with Indian society. His belief in the benevolence of the British Empire seemed to blind him to the deep-seated grievances of the Indian people. He acknowledged the sensitivity of Indians to perceived slights against their dignity, suggesting that the disconnect between the British and Indians was not merely a failure of policy but a profound misunderstanding of the cultural and emotional landscapes at play.