Exploring the role of reading rooms in shaping the DMK’s political landscape and community engagement.

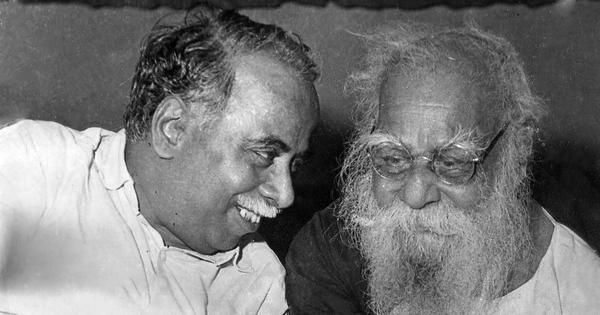

Periyar’s vision of a social organization being more effective than a political party in uplifting Tamils resonated strongly within the Dravidian movement. The DMK, mindful of Periyar’s concerns about electoral distractions from reform activities, focused on core issues in its early days, conducting numerous public meetings. These gatherings included seven conferences dedicated to women’s empowerment, specifically advocating for reforms in Hindu laws across Madras State, along with a conference addressing the Tamil language in Coimbatore.

To further its engagement with the public and its party members, the DMK established padippakams, or reading rooms, adjacent to its branch offices. Annadurai recognized these reading rooms as essential for promoting political ideas, engaging with the community, and bolstering the party’s support and cadre base. The activities in these spaces extended beyond mere reading; they included the publication of journals, pamphlets, and books, as well as performances such as street plays and dramas.

The evolution of reading practices in colonial Tamil Nadu played a significant role in this context. Initially characterized by oral traditions, reading often occurred in communal settings, with palm leaf manuscripts serving as the primary medium. Limited access to these manuscripts meant that reading was typically guided by scholars in public venues like temples. However, the mid-19th century brought a significant shift with the advent of print culture, following the lifting of restrictions on Indian-owned printing presses in 1835. Although printed books became more accessible, traditional scholars remained skeptical, leading to a coexistence of oral and print cultures.

This tension between traditional and print-based reading intensified in the late 19th century, as scholars reliant on oral traditions felt challenged by the authority of standardized printed texts. Despite the gradual penetration of printed materials into Tamil society, oral recitation and memorization retained their influence, especially among traditional scholars who were hesitant to embrace the shift to print.

As the early 20th century saw the rise of a middle class, silent reading emerged as a popular practice, particularly among younger readers who began to read novels privately. This shift represented a departure from communal oral practices, as silent reading became associated with leisure and a middle-class lifestyle. However, oral and group reading continued to thrive among lower classes, who still gathered in public spaces to enjoy popular literature.

By the 1970s, literacy rates in Tamil Nadu reflected a complex picture, with about 30.9% of the population literate. The reading rooms thus served dual purposes: they trained party cadres to articulate the DMK’s ideology and acted as forums for public discourse. Monthly public-speaking workshops were conducted by senior party leaders to develop young cadres’ abilities. Additionally, these spaces functioned as night schools for children and adults seeking literacy.

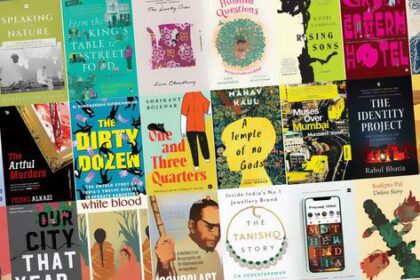

The reading rooms aimed to disseminate the Dravidian-Tamil ethos of social justice and the significance of the Tamil language and its cultural heritage. They provided access to a range of materials, from pamphlets to newspapers, promoting an inclusive environment for all non-Brahmin lower castes and Dalits. Personal accounts, such as that of Tamil scholar Suba Veerapandian, highlight the accessibility and impact of these reading rooms in fostering community knowledge and political consciousness.

In various parts of Madras, reading rooms became vibrant centers for knowledge sharing and cadre training. Regularly scheduled readings from newspapers and journals were conducted by party members, typically from non-Brahmin backgrounds, ensuring a continuous flow of information and engagement within the community. These spaces played a crucial role in the DMK’s political journey, shaping not only its ideology but also the social fabric of Tamil Nadu.