The Smart Cities Mission raises concerns over the centralization of urban governance and local democracy in India.

The Smart City Mission, introduced by the Indian government a decade ago, has significantly altered the landscape of urban governance through the implementation of Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs). These SPVs, designed to establish separate legal entities for planning, executing, and monitoring urban projects, represent a shift towards a more centralized approach in managing city affairs. By creating these entities, the government aimed to facilitate private funding, allowing for a more flexible project selection process and expedited decision-making. Unlike traditional municipal councils that require broader approval for initiatives, the boards managing SPVs can operate independently, raising questions about the role of local democracy.

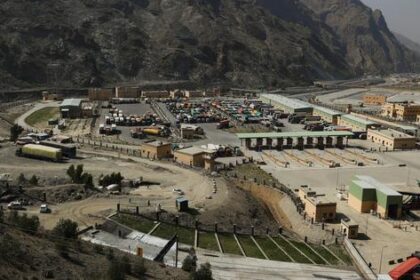

In various states such as Punjab, Madhya Pradesh, and Karnataka, cities have made substantial investments in infrastructure improvements, including enhanced water supply and sewerage systems, as well as smart roads. For instance, smart road initiatives in Mangaluru have reportedly improved pedestrian safety and encouraged community involvement. Additionally, digital solutions have been implemented to track waste collection and enhance urban aesthetics through beautification projects. However, this diverse array of initiatives often surpasses the conventional project scope of municipal corporations.

The establishment of SPVs raises critical concerns regarding the governance structure in Indian cities. These entities are created under the central government’s directives and are structured as companies led by a chief executive officer, alongside a board comprising state and local officers, independent directors, and occasionally elected representatives. Nevertheless, the reality is that these SPVs frequently operate as public institutions, with their leaders often being state-level bureaucrats. This dynamic fundamentally shifts the balance of power between various levels of government, fostering a centralization that undermines local democratic processes.

At the national level, the central government has been able to impose its vision on urban development, prioritizing projects like Integrated Command and Control Centres and digital waste management initiatives. This imposition often overlooks local contexts and the specific needs of cities, as decision-making increasingly becomes the domain of bureaucrats rather than elected officials. In this centralized framework, local politicians find their influence diminished, often feeling sidelined in favor of technocratic governance.

Despite some degree of state control, variations exist across regions. In Punjab, for instance, the state maintains comprehensive oversight of SPV projects, while in Madhya Pradesh, these vehicles are more closely integrated with local municipal structures. Meanwhile, in Karnataka, SPVs enjoy financial autonomy yet operate independently of city governance. This trend toward centralization is further reinforced by the push for digitalization, which is framed as a means to enhance efficiency in urban management.

The role of local elected representatives has been significantly curtailed under the SPV model, with many councilors feeling powerless in discussions about urban projects. This dynamic has led to a depoliticization of urban governance, viewed by critics as a regression for urban democracy. Although the Smart City Advisory Forum was intended to facilitate participatory governance, its actual influence on project selection has been minimal.

While the trend of centralization in urban governance is evident, it is important to recognize that local politics is not entirely absent. In some instances, regional politicians and local leaders still manage to influence project decisions. Furthermore, the challenges facing urban democracy in India have historical roots that extend beyond the recent developments associated with the Smart City Mission. Even decades after the 74th Constitutional Amendment aimed at enhancing urban decentralization, many municipalities still lack regular elections, underscoring the persistent challenges to local governance in the country.