People once went to the hills to slow down.

Now the hills slow everyone down—by force.

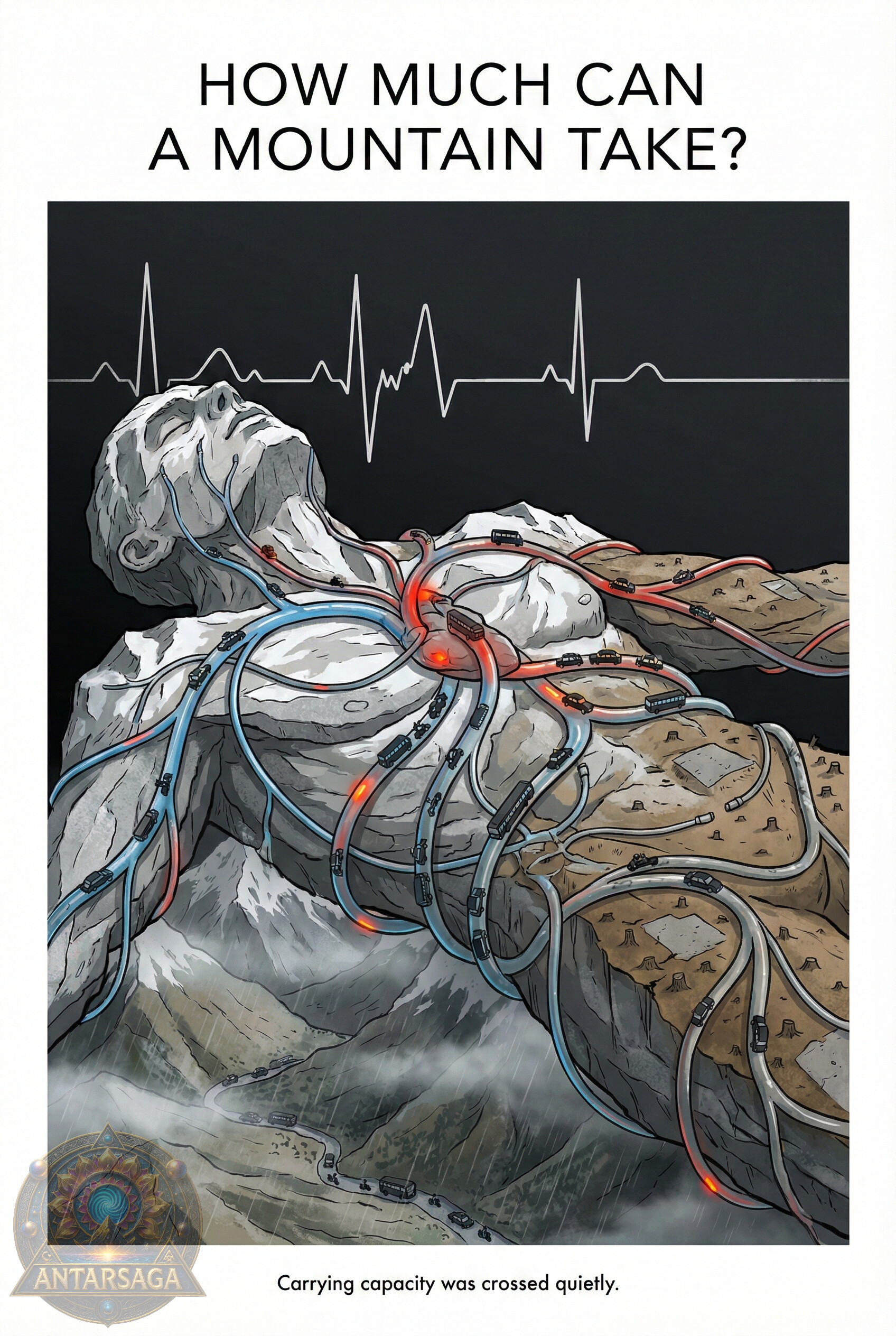

This winter, Mussoorie did not freeze from snow alone. It froze because the town has quietly crossed a line no one dares name: carrying capacity. Roads choked. Ambulances waited. Children reached school late. Parents reached offices exhausted. Tourists reached… nowhere.

And everyone blamed traffic—without acknowledging that traffic is only the symptom.

The disease is deeper.

The recent nightmare of tourists stranded for hours in Manali, sleeping in cars without food or water, made national headlines. But for hill towns, this is no viral exception. It is a daily rehearsal of collapse—played out in Mussoorie, Nainital, Shimla, Auli, Chopta, Joshimath, even interior villages like Sankri.

The irony is cruel: the smoother the highways become, the harsher the choke at the destination.

With the Delhi–Dehradun Expressway now operational, the mountains are no longer distant. They are just “a weekend away.” But towns perched on fragile ridges were never designed for expressway logic. They were built for feet, mules, seasons—and patience.

Instead, what arrives is velocity without pause.

The Slow Death of a Hill Station

There was a time when reaching Mussoorie took an hour.

Now it takes three—on a good day.

What was once seasonal chaos has become year-round suffocation. Even January snow weekends now resemble peak summer gridlock. For long-time residents, this decline is not abstract—it is lived daily.

The quality of tourism has changed. So has the quality of life. A town once known for quiet dignity—oak trees, stone cottages, mist and restraint—has become a honking, diesel-choked stretch of asphalt where trees disappear silently.

Sometimes literally at night.

There are whispers, and sometimes evidence, of trees being weakened deliberately—roots damaged so they fall conveniently during rain or snow, clearing space for construction or parking. The law is informed. The law looks away. By morning, another tree is gone.

This is not development.

This is slow vandalism, disguised as progress.

The Myth of More Parking

Every few months, the same solution resurfaces: build more parking.

But where? On slopes already stripped of trees? On land where springs once fed valleys? On curves meant for breathing, not braking?

Parking does not reduce traffic in hill towns—it invites it. Roads here are narrow by geography, not mismanagement. Cutting more trees is not an option; the Himalayas have already paid enough for impatience.

Yet cars keep arriving.

Because stopping them is uncomfortable. Because regulation invites protest. Because short-term earnings feel easier than long-term thinking.

So instead of restraint, we practise collective denial—and call it development.

When Solutions Become Showpieces

Mussoorie tried. It really did.

Shuttle services were launched with fanfare. Lakhs were spent on kiosks, signage, parking zones. On paper, it looked flawless. In reality, it collapsed quietly.

The shuttles barely ran. Parking lots lay underused. Kiosks became relics of intent without execution. Even the electric golf carts meant to reduce congestion now add to it—circling tourists while locals wait at the margins.

Not because the idea was wrong, but because it was imported without adaptation.

This pattern repeats. Officers arrive with enthusiasm and urban logic, apply templates from plains cities, stay briefly, then leave. Vision without memory. Policy without context. Locals remain—with half-implemented plans and full consequences.

The question is simpler than any master plan:

Why are private tourist vehicles allowed to enter when there is no parking, no booking, no plan?

Why can’t vehicles be stopped 30–60 km before town limits? Why can’t local taxis and shuttle systems complete the last mile? Why isn’t the entry linked to accommodation and parking proof ?

These are not radical ideas. They are common sense—now treated as inconvenience.

When Emergency Loses Meaning

An emergency, by definition, is short of time.

But what happens when even ambulances are told to “leave three hours early”?

In the past year, at least two people reportedly lost their lives because emergency vehicles could not navigate gridlocked roads in time. Hospitals did not fail. Roads did.

This is not just about tourists. It is about residents—students late by hours, commuters drained daily, elderly people afraid to step out. Wrong-side driving has become normalised bravado, mistaken for hill-driving “skill.”

There are days when locals choose to stay elsewhere rather than attempt the journey home. A town should never feel like a trap to those who live in it.

The most unsettling part is not the chaos itself—but how casually it is accepted.

“It’s peak season, what can you do?”

As if seasons justify paralysis. As if negligence were weather.

This is not nature’s doing.

This is ours.

Greed Without Villains

It would be easy to blame governments. Easier still to blame tourists.

But the truth is more uncomfortable.

Unregulated crowds suit many. Illegal hotels thrive. Roadside parking earns cash. Scooter rentals spike. Day-trippers clog roads, spend little, leave chaos behind.

Rules, when enforced, face pushback—often from locals themselves.

Everyone benefits—until everyone suffers.

This is not malice. It is slow greed. The kind that feels harmless until the water boils. And somewhere between profit and paralysis, a hill town is being killed—one tree, one jam, one quiet night at a time.

The Climate Is Speaking Too

While we debate parking, the mountains are changing.

Snowlines climb higher. Winters shrink. Snow melts faster, recharging little. Dry winters follow violent monsoons. Cloudbursts erase roads widened months earlier.

The ecosystem oscillates between extremes—too dry, too wet.

So does tourism—too empty, too crowded.

Nothing is balanced anymore.

Perhaps the mountains are not angry.

Perhaps they are simply exhausted.

What Needs Rethinking—Not Just Reacting

Hill towns cannot be managed like plains. They need filters, not funnels.

Vehicle caps during peak days—enforced well before entry.

Mandatory park-and-ride systems from foothill towns.

No entry without accommodation and parking proof.

Strict, consistent enforcement against wrong-side driving and illegal parking.

And honest conversations about carrying capacity—without fear of being called anti-tourism.

Tourism cannot be infinite in finite spaces. Development that destroys its own foundation is not development—it is demolition in instalments.

This requires restraint. Continuity. Listening to locals. Accepting inconvenience today to preserve livability tomorrow.

A Question the Mountains Are Asking

The Himalayas are not collapsing dramatically.

They are suffocating quietly.

If every new road only brings more vehicles,

if every solution avoids limits,

if every inconvenience is postponed to “after the season”—

Then one day, the mountains will not block us.

They will simply stop receiving us.

Not with landslides.

Not with warnings.

But with silence.

The kind that comes when a place has been loved to death.

And when that happens, all the expressways in the world will lead nowhere.

— Written from Mussoorie, but true of every hill town